Monday, December 14, 2009

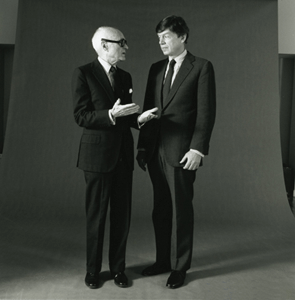

The Philosopher architect: Philip Johnson interview about his work and life with academy of achievement

Sharearchitect/artist: Philip Johnson

interview title: The Philosopher architect

interviews compilation no: T-22

interview format: text

date: February 28, 1992

appeared in: Academy of Achievement

interviewer:

photo by:

courtesy: http://www.achievement.org/autodoc/page/joh0int-1

Interview Details:

The Philosopher architect

What made you want to be an architect?

Philip Johnson: I don't know. Because I couldn't do anything else probably. I wasn't very good at anything.

My mother was interested in architecture. She wanted a house by Frank Lloyd Wright when she was young, but my father didn't see it the same way, naturally, for obvious reasons, so we compromised by not having one. I suddenly realized in the middle of my political work -- ran for the local state legislature and didn't want that. It didn't work at all. I was a lousy politician, terrible, had stage fright, everything wrong. I was like certain candidates for Mayor in New York, but we won't go into lots of things. So I said, obviously, I had missed my calling. So at the age of 34, I decided to really be serious about architecture. So I went to Harvard at 34. You see, my problem always was I couldn't draw, so I knew I couldn't be an architect. Harvard didn't care whether I could draw or not. It seemed like a good idea. By that time, I'd worked for some years at the Museum of Modern Art on architecture, so I decided what the hell, I might as well be one.

I majored in philosophy at Harvard, and I didn't know if I wanted to be a teacher or a theoretician or just what, but I was always interested in art and architecture to look at. I was mostly interested in ideas and politics and world events. So I suddenly realized -- in the middle of my political work -- I had missed my calling.

Was there an event, a moment early on that influenced you?

Philip Johnson: Yes. I was a young man, much more inspired than I thought I was. You don't know what you're doing when you're young.

You get very excited about something but you don't know you're getting excited about it and you think everybody's the same way. I don't see how anybody can go into the nave of Chartres Cathedral and not burst into tears, because I thought that's what everybody would do. That's the natural reaction I had. That and the Parthenon -- one in 1919 and one in 1928 -- gave me the realization that I had to be in architecture in some way. Those events were sort of a Saul/Paul conversion kind of a feeling that determined me to play some part in architecture. So when I joined the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, I started the Architectural Department and worked there for some years and wrote a book. When I went to Harvard, it was taught in the school, so I was allowed not to take that course. It was very funny.

How old were you when you saw Chartres Cathedral for the first time?

Philip Johnson: I was 13.

So I thought, my goodness, if a kid like me can get this excited, I didn't think it was anything unusual. Mother didn't either. She was interested in art, she took me (to France during) the Versailles Treaty years and I remember saying to myself, and I wrote it later in letters, that if I lived in Chartres, I would turn Roman Catholic to enjoy that cathedral, and if I turned Roman Catholic however, I would go and live in Chartres. Because how else could I exist without this closeness to this particular thing?

Tell me about the Parthenon.

I first saw the Parthenon in 1928. By then I knew more about architecture and the history, but the actual presence of those stones was entirely different than the books. If you've just seen pictures of the Parthenon you haven't the slightest idea of what it is. But to be on that particular hill, with the other great hills around you, and be standing with those stones practically in your hands -- because a lot of them are falling down -- was an experience that was second only to Chartres. I wrote an article at that time saying there was a pre-Parthenon Philip Johnson and a post-Parthenon Philip Johnson, because that was the strongest single point of my learning about architecture. I was already 22, I should have known more. I should have known in 1922 when I was 17, 18, that I was going to do that. But I thought everybody did, so I'd do what I was interested in at that time, which was music, philosophy and the Greek language. I thought one of those three I was going to be into. I had this terrible thing happen to me at the Parthenon, but it wasn't until I was 34 that I had sense enough to go and get my education. Education's terribly important. But at the time, I would have none of education. It was all feeling and being converted to a dedication.

What were you like as a young man in Ohio?

Philip Johnson: A twerp.

I was a spoiled brat. I was insufferable, very unpopular at school, very unpopular with the girls. Couldn't dance, couldn't mix. I was a loner and family practically gave up on me, wanted to give up on myself. You know the usual, "Oh goodness, what good am I?" bit, that every young person goes through, but I thought it naturally was unique and that I alone suffered. I read books on suffering, The Sorrows of Werther and so on. I was a lousy kid. It was when architecture hit me that I became more sensible.

What kind of a student were you?

Philip Johnson: Good. Amazing. I was a patchy student.

Sometimes I couldn't do something like write. That was a writer's block kind of thing, exaggerated up to a disease. So I flunked everything to do with writing or any expression in writing. Of course, it seems funny later that I did produce a book or two, but at that time, it was an unbelievable hurdle. There were no psychiatrists in those days, so I finally went to a nerve specialist. You're too young to remember that they were called neurologists or nerve specialists. They were naturally shrinks, but they didn't have the Freudian overtones. He told me I was sick. I was manic depressive. Naturally, I was delighted, but I was in tears most of the time. Somehow you get over all these things. I never thought I would. It's the end of the world again, you know. But early unsuccesses shouldn't bother anybody, because it happens to absolutely everybody. Every one of us goes through this and it's a funny thing that they don't tell you when you're young that depression now and then is perfectly normal, that sense of failure is also normal, but so is a sense of excitement and delirium normal. And I may be talking only for artists, but I doubt it. I think everybody has these inadequacy feelings that are helped by religion or psychiatry or just plain grow up. That's all I did, was just grow up.

Any books or teachers that helped you or influenced you?

Philip Johnson: Yes, my philosophy professor at Harvard, Rafael Demos. He was a Greek and we worked on Plato together a good deal. He was personally a great influence, but he didn't help my architectural feeling at all. I was going to teach philosophy. The head of the philosophy department at Harvard said, "Why don't you come and teach? Become a professor." Well I knew I wasn't any good at that! I got turned off of that by Whitehead, the great philosopher. He took me into his class, but I was hopeless. Couldn't understand the simplest things, apparently, and that got me off philosophy.

Any heroes, any role models?

Philip Johnson: That I knew personally? No. I must have, because I'm naturally a hero-worshipper type. Out of history, Napoleon, for instance. I still believe in the "great man" theory of history which, of course, is so much against the historiographers today that I never dare say so in public. I've got a new hero right now, General Schwarzkopf, simply because he's down to earth and straightforward and very, very funny. The man has an enormous sense of self-assurance and enormous competence in handling people and a very fast mind. Those are the things I admire most in people, and he has them all. But that's just a passing love of the moment. I had some bad times too.

My hero-worship got around to Huey Long. That'll suprise anybody, because Huey Long is a forgotten figure, a populist from the South who wanted to save the world from Roosevelt and from the Depression. Things were bad in the '30s. That I couldn't stand. I said, "What is it? We've got plenty of wheat and grain and trees, and why is there hunger?" Of course there was in those days. This depression hasn't gotten to that stage yet. But that was bad at that time. So I said, "What do I do about it?" I didn't want to be communist, which seemed to be what one's intellectual friends did. So instead, I became what was later called fascist, but it wasn't in those days; it was populist, and Huey Long was going to fix everything. So I drove down and met Huey and said, "What are we going to do?" And one of his people said to me, and I'll never forget this, he said, "How many votes do you control?" I was only asking whether I could even work with the man! In other words, he was so individual and chaotic that there was no way of getting along. So I came home and he got shot and that was the end of that. He was quite a figure.

I recall your being interested in Father Coughlin.

Philip Johnson: He was my substitute for Huey Long. Father Coughlin was more of an intellectual of course, but also not as basic, not as good.

You could not have graduated from college at a more challenging or unsettling time -- economically, politically, socially. It was the start of the Great Depression. What were those days like?

Philip Johnson: Tragic. I didn't see how art fit in. It was too close to me, the farms and people in debt and people plain hungry. You wouldn't believe it was possible in this country. Roosevelt didn't seem to be doing enough, although I voted for him six times... no, he didn't run that many times... but he was a great man. So art was not so important in those years, all of the '30s.

What were you looking for during that time?

Philip Johnson: Hero worship. Speedy solutions. I didn't see why we shouldn't get things going instead of dithering all the time and talking so much. The first time I joined any political thing was a milk strike in Cleveland. My farm was nearby and I fought with the farmers against the milk companies. Took radio time and made talks. Was finally threatened off the air by the milk companies. They got to the head of the station and said, "Don't sell that man any more time!" I hit a nerve anyhow. I had fun. I doubt if I helped the farmers much

Any lessons from those experiences in the '30's?

Philip Johnson: I put it out of mind.

That's what I like, is causes. I always overreact. If I go religious, I go on my knees for days, that kind of thing. That was a very short interval, but the cause was a good one. Once I discovered architecture as a need of my nature, then of course that enthusiasm knew no bounds and it's been the same ever since. The turning point was 1939. And ever since then, art is the only thing I've been alive for. I spend my waking hours. There's no such thing as leisure time, for instance. If your work is architecture, you work all the time. You wake up in the middle of the night. I got a wonderful idea last night! Still working in Berlin on one of those things and I know just where that window is going to be. I'm varying between that shape and this shape. I enjoy it more and more all the time. I've got to hurry now.

Architecture sometimes seems like politics or religion. It's full of movements and orthodoxies and heresies and controversy. You always seem to be right in the middle of it all.

Philip Johnson: I love that, you see. I didn't lose that just because I switched from philosophy to architecture. I'm still a thought kind of an architect more than a genius type. I'm not a genius. There are some, and I love them, but I like the give and take and the change and the prophesying what's happening and catching onto the next train by the caboose. Caboose? You don't have 'em anymore do you? Just seeing what's going to happen, and figuring it out with the young. Where are we at? Every one of my articles is a struggle, a "where are we at?" thing. History's in the making right now. It's very exciting and it's changing all the time. So to be in on it is my biggest pleasure. I always thought everybody felt that, but again, I guess everybody's different.

What brought about this turning point in 1939?

Philip Johnson: The war. It was pretty obvious to me what was coming and I didn't have any part in it. I wasn't connected. I loved the Germans and I didn't see any particular sense in it, but my country was terribly important and I realized that we weren't in danger perhaps, but that the next battle line was the war. Of course I wanted to be in it and I finally succeeded, but I was too old. They called me Grandpa. But they did draft me and I had a very nice time indeed.

What took you so long?

Philip Johnson: I was a damned fool. That's not hard to explain.

Everybody's their own kind of a damn fool. I'll bet even you think now and then of opportunities missed and think that you could have done perhaps better? I'm full of regrets. Piles and piles of them, but you must not let that bother you. You'd just shoot yourself, which would be nice, but it doesn't pay out. What's the point? So if you can find something to do the way I did, then it keeps you alive. That's the reason I'm alive and active at 85 with lots of work and traveling all over the place. I'll work until I drop, which will be a long time from now.

What were some of the pressures that affected you? What were some of the things you had to overcome?

Philip Johnson: The political side, the war. I was not an athletic type, and the other soldiers were children half my age. It was a traumatic experience. Would I make it? It tested me as nothing else could.

The military is the most important single profession in this country, except for architecture. If it weren't for the military, I couldn't do architecture. So I admire the military very, very much. That isn't popular either among Harvard intellectuals. You know, you try to get to get out of fighting in wars if you can. No! That got me out of my namby-pamby spoiled kid position in the world. My family had money, which is a very bad handicap. I didn't realize that. I thought it was kind of nice. I had a car when I was a private in the Army and drove up to Washington every single night from the camp. Terrible.

The arduous part of the day was so arduous and so collapsing. That I lived through it at all was a triumph. It was the most wonderful thing that ever happened. That was a moment of the purest pleasure that I could get along with these kids. They didn't hate me. They did call me grandpa, but I wasn't condemned the way I was condemning myself all the time because I wasn't physically fit. I was a stupid intellectual, you know. The type that wore glasses and went around reading. When I had to stay up all night in the army watching a machine or something -- they put you on the funniest duties -- I read Madame Bovary in French, you see. Just it was easier and it was a lovely language. I can't read it now, but I mean, it was so concentrating, that atmosphere in a camp.

I'll tell you what happens when you get crushed together like that with a bunch of men: all their character comes out much quicker, much sharper. I led a lonely life with my family. I was a spoiled kid. And then to be thrust in with all these decisions that you have to make every two seconds with the armed forces, anyway, whether you're with your captain -- whom we naturally hated because he was an evil figure -- or the lieutenant, which was a hero figure because the captain didn't like the lieutenant at all. If you are a novelist, how could you do anything except join an army? So I agreed with Napoleon that it was fine to fight for your country.

And then you came out and began your career as an architect?

Philip Johnson: Yes, right away.

And had some trouble passing the New York State exam?

Exams are so stupid. I couldn't be bothered to work for them, so I kept flunking them. They were too simple-minded. So I went to a cram school. The cram school of course said, "You idiot, look at that piece of paper." I said, "Yes. It's a fine piece of paper." He said, "You've only got six lines on it." I said, "Yeah, the paper's so beautiful, what do you want to spoil it for by covering it with all these lines?" They said, "Look, you've got to pass the exam. You stop your damn theories and cover the sheet with extra trees, then. It doesn't make any difference, just fill it up. Put more bricks in or something." And then another clue, "How do you know how to get into that building?" And I said, "It's right here." They said, "No, you take a red arrow. And it doesn't matter if it's the only red thing you've got on the sheet, put that in, so the examiner will see it." I said, "Oh, I see, he knows where to go in." Those simple little tricks I had trouble at. I passed it by doing -- they wanted a house in the suburbs. So I did it, just out of my memory. I took a suburban house. Don't like them, would never build one, hated the whole thing. I used to go to an exam and do what I wanted to do. Of course they didn't like it, because I was always doing something different from other people. Anyhow, by knuckling under I had no trouble. You learn lessons, you see. Always give in. I mean at the proper moment -- when you have to.

Is that what it takes to be an architect?

Philip Johnson: To be an architect, you've got to know people. Like most professions. You have to know people in order to get the next job.

As the richest and the greatest American architect said, "The first principle of architecture is, get the job." In other words, if you aren't personable enough or persuasive enough to get the job, you'll never get anywhere. Another important thing, it's hard to tell anybody what's important because it's inside you. Alas for education. Education doth not help you. You can read all the books in the world and make terrible designs. I had learned professors that I worshipped. Russell Hitchcock. He was a great, great historian of architecture. I wanted to be an architectural historian, that was one of my passing fancies, but I wasn't any good, and this guy was great. And then he tried to build a building. Disaster! In other words, it takes something else besides intellectual prowess. Harvard will never help you become an architect. Never. It takes what they laughingly call genius, but there are only a couple of geniuses once in a while like an Einstein or a Frank Lloyd Wright. No one can aspire to that. That either is God-given or not. There is nothing you can do about it. It's just too big. So you've got to have at least a spark. I'm no Frank Lloyd Wright, that doesn't bother me anymore. It used to, but I was never the genius. It was interesting though, to see who would be and who could be. I foresaw a lot of kids' careers that are now on the top, and I foresaw. I could tell when they were younger that they were going to be good. "I never could see why you like Frank Gehry's work," and I said, "You wait." And in ten years, indeed, he's the leading architect of the world. That kind of thing gives one a certain pleasure.

All of my advice is straight to all kids, "Should I be an architect?" I say "No." Always say no, because if you can help it, don't. Go into something that'll make money, if that's what most Americans seem to want, me included. Just don't bother with architecture. You remember when a kid came up to Mozart and said, "Should I write a symphony now, Mr. Mozart? Do you know what I do?" Mozart said, "No." And the kid said, "Why do you say no? You wrote a symphony when you were my age," and he said, "Yeah, but I didn't ask anybody." In other words, if you're going to be an architect, you'd better have a feeling inside that you can't help it. A "calling" it used to be called in the days when religion was a little more popular.

What about your meeting Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe? How did that influence you?

Only Mies influenced me. Le Corbusier I met. He was a nasty man, but obviously a genius. You don't have to like the people just because they're geniuses. Mies and I got along better and we became pretty close. I worked with him on his greatest building here, the Seagram building, which was kind of fun, but again, you can't be a hero-worshipper and be an uncommon architect; you've got to be your own man. So I split with Mies and did a different kind of work.

Can you say something about what inspires an architectural design? What goes through your mind?

Disaster. Agony. You're a writer. You know what a thing that blank piece of paper is. That's the ultimate horror. After about an hour of sweating over nothing, you finally, crabbedly write the beginning and that's what I do, what all architects do. Then you make a very tentative drawing and that's terrible. But somehow you get interested. Then you start a different idea and that's no good, but what about that idea, what about that idea? And your whole day passes in flashes because -- it's not a flash of genius in my case, but it's a flash of getting something on paper. Very funny.

There's no talking about it though.

The Glass House has been called one of the most influential designs of this century. Why?

Philip Johnson: I don't know. I didn't know it was.

It's the most photographed house. Bothers the hell out of me. I'm supposed to live there and then people come and look at you all the time. It's annoying. I don't think it is. That was the time when I was working with Mies. Mies's ideas are perfectly clear there, of using nothing but glass for the walls. Seemed the natural thing to do. Most people didn't think it was so natural. As they said in the local papers, "If Mr. Johnson wants to make a fool of himself, why doesn't he do it in somebody else's town?" Oh dear. Of course, I enjoyed all of that. I enjoyed the battle.

How important is the battle and the struggle? Can you create without it?

Philip Johnson: Maybe I can't.

Maybe the battle is the thing. Like a horse in wartime, it smells the gunpowder and gallops off to war. Maybe it's the charge and the challenge that makes you work. That's why you can't talk about these things. It's just that it satisfies something needed for living that nothing else will. And the best days in the world today are spent alone in my study with a piece of paper. Great satisfaction. In the evening I can relax and watch Dallas or something.

Do you have to work alone?

Philip Johnson: Oh my goodness yes. The reason I like architecture against painting is that I don't have to be alone, because every ten minutes there's a disaster and they say, "Well I don't think you can take that piece of steel and do that with it. It'll fall down." Well that has nothing to do with art, but it takes a lot of time. So when I mean being alone, I mean when you're doing your so called creative work, you have to be alone.

How important is it to be able to collaborate with others?

Philip Johnson: Very. I'm a people person. I don't know how painters or writers sit there and work month after month. I don't know how you go to the woods in Maine like E.B. White and just sit there. I'd go stir crazy. I can't work if I'm alone. If I take a vacation, I can't work. Therefore I don't take vacations. It's so silly to sit around a beach for God's sake.

What is the feeling of having designs become reality? Seeing your buildings?

Philip Johnson: Now that's another pleasure, to see it come up and watch other people's faces and have them appreciate it. But everybody wants that. That's called the desire for fame. Every movie star has that feeling of wanting to be accepted and be praised. That's a natural ambition in the world. A sense of conquest too. Very, very satisfying, but the trouble is, you mentioned a few very nice buildings, but what about the ninety percent of the other buildings? There's two sides to every one of these coins and I certainly won't talk about those. I only talk about the ones that did come out well.

What are your disappointments?

Philip Johnson: Most buildings, if I'd had another chance. If somebody had only given me that extra money that I needed at that particular point. If I only hadn't made the decision to give in when I thought it was inevitable and it wasn't. Was it really inevitable that I give in on this point or that point? That's the sin against the holy ghost. You're betraying yourself. And how many times do you do it for expediency? It used to be the old excuse, I remember. I haven't used it recently, but I can see it: "I took that job and I knew it was a lousy job," they say, "but I had to keep the kids in the office, at work. I couldn't fire them because of the Depression and so I had to feed them. Therefore, I took that job, yes." You didn't have to take that job. But you do that, you compromise -- one does I mean. You do, and that's what you're ashamed of. I'm only proud of the buildings I built in my own place, really, because there was nobody to stop me, no financing, no troubles, and if they're bad, at least I don't know it. I go on building little houses around, in and on the place.

What building are you most proud of?

Philip Johnson: I don't know.

I know the ones that are the greatest triumphs, like the Dumbarton Oaks Museum in Washington D.C. that I worked on with the owners. It was a real collaboration and there was no budget, no money involved. It was just, "If we like that better, we'll do it that way." So I had total freedom and it was a simple project to build a little museum, and the owner and I worked together and it was pure delight from beginning to end and it came out very well.

You've designed buildings from the Glass House to the Crystal Cathedral to the AT&T building. Is there a difference between designing a house and designing a skyscraper?

Philip Johnson: It's more difficult. Because every decision you make makes such an enormous percentage difference in the looks. If you get a good plan on a skyscraper, you've got to get somebody's computer -- not mine -- and click it through and it reproduces all the plans all the way up to the hundredth floor. So you have a few basic decisions and then the battles begin. Because if you get into that kind of money everybody has something to say and everybody knows better than the architect. Every kind of consumer becomes a part of the business. You never know what's going to open up next to stop your design. AT&T! The battles! It's lucky it came out as well as it did.

There certainly was controversy with that.

That's peculiar, isn't it, because there's nothing very strange about the building, do you think? I shouldn't be asking you. It looks pretty ordinary to me. I put a funny top on it. But not funny, people call it the Chippendale top. I didn't know about Chippendale at the time. I see now what people mean, but I didn't know. It was just a way to end the building that people would notice and would decorate the building so you'd know it from other buildings, with a cut-off, like that. You don't miss the building if you never see the top, but that's natural to make a building be seen. The Chrysler building -- wonderful top. They spent all their time on the top. There's no middle, just dull windows. But with a top like that, that's going to be a monument for all of history. So I though I'd like an interesting top. Boy, my friends in the company weren't as pleased as I was, but we got it. They wanted a new way of looking at the world. I said, "Well this is different," so we built it. Seagram's was just the opposite. Mies had the confidence of the owners and he built it and, it was their idea, to build it in bronze. I mean, there cannot be anything more expensive in the world than bronze. You notice it's the only one, but they said, "Fine. If it's the finest material, let's use the finest material." So that of course was a very pleasant job.

What do you have to take into account when you're designing a building? Aesthetics? Function?

Philip Johnson: Yes. That's a very good question, because there are certain things that you damn well have to take into consideration and more people should. It was hard for all of us, but without that, you can't go onto the creativity of a structure. You've got to know what stands up in present-day technology and what doesn't, or your fantasies will be fairy stories and not designs for buildings. Another thing you have to know is function. Modern architecture was founded in functionalism as a goal and, as much as I fight that as the only goal, it became the only goal, and that's bad too.

The only goal is building a beautiful building, but if you don't know your functions, if the Seagram building didn't work and make piles of money for everybody, it wouldn't be a success because all skyscrapers are money-making machines. So a function of the building, what would rent the best, is always on your mind. You can say, "Oh it's just commercialism," but that commercialism is our non-religion. It's our custom of the day and that's what our period's all about: consumerism and business. The business of America is business, somebody said and, strange as that sounds, that's what it is. So you damn well have to be functional in all your work, even a church. You can't ignore function. I love to do churches because, of course, there is the spatial feeling of God that you have going for you that's a little more interesting function than the layers of office cubicles.

You have to know those things. You have to know structure, and you spend nine-tenths of your time on that. You say you know structure, but do you know connections? What happens when the water gets in that little place? Only years and years of experience... but that's nothing to do with the art. You've got to know all of that before you start. Painters have it easy; they've got to know what kinds of pigments will last. They don't know that even sometimes, but even that's not necessary. You repair a picture if it's bad, but in architecture, it falls down. That's a sociological crux. Then you've got the permits and things to go through with city hall that drive you up your wall. Then you have the clients. The care and feeding of clients is really one of the main obstacles, because you always have a client with some preconceived idea of what a house looks like, and all you want him to do is leave a check and go to Europe for a couple of years. Or leave two checks. But alas, life isn't simple. If it were, more people would be better architects.

You said "You cannot not know history." What did you mean by that?

Philip Johnson: We were in a period in the early '50s or '40s that thought the whole thing could be solved by technological means. Science will take care of everything and no input of cultural history was of any importance. I never believed it and I still don't. So I claim that you've got to have a feel for the history of architecture. I started out as an historian, so probably I was just pushing my own interest. I felt that you can't not know it because it's there all the time, it's around you anyhow. If you ignore it, then you're denying the very input your buildings have to have. So you can't not know it. It's a good remark. I plastered it on the wall at Yale when I taught there.

You've been described as the most influential American architect in this century and as an enfant terrible. Which description fits you best?

Enfant terrible. I'm not the greatest influence at all, but I am nasty. I have a very bad reputation for always saying tactless remarks that are much better not being said. I really don't understand that. To me, I just tell the whole truth, but perhaps that isn't the right thing to do at that moment. But, I'm still here. If you can prove to me that that's hurt my career terribly, then I'd take it more seriously. But in spite of the horrible mistakes I've made in my life, well, I suppose some of them were inevitable, but you didn't have to be such a damn fool, Johnson. Still, I'm here. I enjoy being an enfant terrible, although I'm pretty old to be an enfant.

What was the worst mistake you ever made?

My worst mistake was going to Germany and liking Hitler too much. I mean, how could you? It's just so unbelievably stupid and asinine and plain wrong, morally and every other way. I just don't know how I could have been carried away. It's like being carried away by a religious revival or something that enables you to cut people's heads off in the next county because they live in the next county. That's not good either. But that I should be psychologically so inept as to be swept along in something so horrible, it really wonders you. How could you? I never found a reason, I never found an excuse, and all I can say is how much I regret it because the racial part of is the worst. I can understand social fascism as done in Italy before Mussolini met Hitler, because that was, "If the trains run on time, let's not do it the communist way, let's do it our way." That made some sense and that's what I was doing here in America. But to be caught up in the racial thing was unbelievable, because like everyone else in the intellectual world, nine-tenths of the people I know are Jewish and the outrageousness of that kind of thing that could happen in a world and I didn't know it?! Where the hell was I?! A Harvard graduate! So much for Harvard! I was just stupid. Just unforgivable. That's the worst thing I ever did.

You've taken your turn as a critic and certainly as the object of criticism. How do you handle criticism?

Philip Johnson: You try to develop a very thick skin. Hard to do. It hurts always. How could they misunderstand me so much?

Do you have any thoughts about the role of the architect in society?

Philip Johnson: I think it's marginal. I don't think it should be marginal. I think it's very important. I think it can influence the world. It can make you a better person if you're surrounded by good architecture, but the world doesn't seem to listen too much to that. They still create cities like Tokyo or Istanbul. Horrible places.

What is architecture's role?

Philip Johnson: Inspiration, like music. History, like music and painting, used to be called ennobling, but we don't care much about ennoblement anymore. What is it? It makes you feel much better. To be in the presence of a great work of architecture is such a satisfaction that you can go hungry for days. To create a feeling such as mine in Chartres Cathedral when I was 13 is the aim of architecture.

If a young person asked for advice about becoming an architect, what would you say?

Philip Johnson: I'd say, "Don't."

I'm not an example for anybody. What to do?

Work at the apprentice system and travel a great deal to absorb the cultures of the world, of the past. You can add a few more to the ones that I had, is the East. The Near East I have learned a great deal about, but not the Far East. That should be included. I don't know how you do this. I don't know how you beg, borrow or steal - even that's all right to me - money to do this kind of fumbling around the world. That's very important, so you can get a feel for the way people actually live. And, you've got to be unfortunately, a salesman. How do you learn salesmanship? It's kind of hard.

How much is inspiration, how much perspiration?

Philip Johnson: About 99 percent is perspiration. Anybody can answer that.

Any doubts about your ability?

Philip Johnson: Oh goodness yes. I'm thoroughly discouraged right now. But that goes with the territory. You see better people around you all the time. Not to be envious and not to take that out in bitterness is a hard lesson, but you'd better, because you can't always be Frank Lloyd Wright. You've got to learn to live in this world just as you live in it. You've got to stand it.

Which awards mean the most to you?

Philip Johnson: None of them mean much. They really don't. What meant something to me is things like this: I was in Europe the other day and I picked up a wonderful new job. That's the reward of being famous. All the fame and publicity and all that seem to increase, and I don't know why, but it's very pleasant if it brings me another great challenge. With that, the next challenge, I can enjoy every single day of my life.

Anything you haven't done that you want to do?

Philip Johnson: Yes, I've always wanted to do one thing, but I knew it wasn't going to happen. So it stays as the dream: to build a city. Cities just grow like Topsy. Look at us here. Total disaster. Doesn't have to be. And I'm very sorry about that.

What's your dream city like?

Philip Johnson: It's all mixed up like Paris and Athens and few other places. I haven't let myself because I worked on some town plans and things that I thought were going to happen and were very disappointing. It's not in the cards these days, so I'm very satisfied by getting this little job in Europe. A few museums and schools that I'm doing. Wonderful time. And I'm doing a church. Very, very small, very unimportant, but very interesting.

Were there any books that influenced you as a young person?

Philip Johnson: Yes indeed, a great many. I got passionate about Nietzsche and Plato. I remember discovering Plato. That was my first love, and then Nietzsche, and I treasure them still in my bookcases. Later on, I became interested in architectural history and my passion in politics. Isaiah Berlin was, to me, the greatest theorist. It's books that really keep the mind filled. Another thing we should advise young people is to read. Read, read, read. If nothing catches your spirit, that's too bad. I must admit that the passion roused by a Plato can have no second. Not even poetry.

Why Plato?

Philip Johnson: He was such a great writer. He wrote the most beautiful prose and beautifully inspiring ideas. It sounds silly to use ordinary words when you get a genius like Plato, but he could think his way around all the plots and describe people and their characters at the same time. He created Socrates. Socrates was an unknown person, but he was made alive by this man's creativity. Now, I do not understand the finer points of Plato. It gets me down, but the comedies, the shorter dialogues can keep you going for a long, long time. Later, I turned on Plato, but that's a long story.

What reached you about Plato?

Philip Johnson: In a way it's like reading the Bible. It becomes so much part of your way of looking at the world that you don't realize it. I just felt moved, let's say, by reading Plato and, I confess, didn't understand it, but he seemed a wise man, saying great things and saying them beautifully. Poor Aristotle was short-changed because he was a lousy writer.

What about detective novels?

Philip Johnson: I read them as President Wilson did, if you please. Detective novels to keep me from committing suicide. They're wonderful relaxation; much better than television. But I only like the American kind and I read all of them five or six times.

Let's talk about modern art. What are the connections between modern art and architecture?

Philip Johnson: Of course there are connections. They're different professions which is why I like architecture better than art, but they're so intertwined that you can't separate them out so conveniently. When I was in college, I met the other man that influenced me enormously like Demos, the professor at Harvard in philosophy. That was Alfred Barr, the founder of the Museum of Modern Art, who got me more than excited by modern painting. Although I had been buying a few pictures, and I loved certain artists like Paul Klee or Pablo Picasso, I didn't have the passion that Alfred Barr did, nor did I have the knowledge. He was the greatest scholar as well as the greatest enthusiast and preacher on art that I know in history. Nobody today can touch him and, with him, I had my eyes opened to greater things in art than I had any experience of.

I had experienced only my knowledge of Mondrian because Mondrian, of course, had a very close connection with architecture. Some painters are more architectonic. The two great ones in recent history are Malevich and Mondrian. If you don't know those people and appreciate them, I don't see how you could be an architect. It seems to me that today, if you don't know the young sculptors or the young artists, that you're going to miss a shape or a form or a passage. You're going to impoverish your work as an architect. It's such a subtle thing. It's one of those things you can't talk about, Why should I be influenced by a vase made by Kenny Price, for God's sake? But you feel it, you feel at the depth a useable, malleable, actual shape. Or, why would I get so excited about my favorite painter for instance, is Caspar David Friedrich. He was a romantic painter. Single men on a dark sea may sound crappy, but I assure you it isn't. If ruined cathedral at sunset may be too appalling to think of, but those pictures, he could do it. Now you'd say, what's the message? I don't know what message, all I know is every time I go to a museum where there are Caspar David Friedrichs, I spend all my time there. Or in ancient art, Piero della Francesca. I'd go 150 miles out of my way just to be sure to see again a favorite Piero because, to me, he was the great Renaissance painter. Others have other favorites, but one is influenced through the viscera. Why Mondrian? Because he used a straight shape that influenced Corbusier and all the modern architects of our time, and Malevich. But you can't see it in romantic painting, you can't see it in religious painting.

No writer has ever been able to explain painting. In fact I gave up reading books on writing. Roger Fry fascinated me when I was young, but he couldn't explain Caspar David Friedrich because he was "significant form" for God's sake, with no significant form in that landscape. So it's best not to talk about it at all. It's magical. That's why they used to say there are many paths to the truth besides reasoning and words and talking. There's mysticism. How do you explain mysticism? How do you find God on your knees in front of a statue. I don't know whether it was God I found at Chartres Cathedral or not. Nobody ever told me that. Those things are mysteries. Why do we like mysteries so much? In this scientific age, we still keep that passion for the unknowable and the risks. Nietzsche, of course, still has my fascination. His strange interest in art and architecture is unique among philosophers. I can say why I like Nietzsche, because he's close to architecture. But painting is something I can't understand. I cannot paint. I cannot think in those terms at all. I've tried and tried, naturally, always tried. Just as many times I've tried to design a chair. This chair was designed by Mies van der Rohe. Well I can't design a chair. I did it a couple of times and they were not only uncomfortable, but very ugly. It's too bad. I feel very incompetent on my bad days and I certainly can't do painting. They're different arts, and yet they influence each other, and I don't know the answer to your question, what is the relationship?

What's the greatest challenge of the next century?

Anybody who makes a prognostication's a damned fool. I've done it and I know it's always, always, always wrong, because you make a prophecy, for a challenge you make an assumption that is based on your experience today. The greatest challenge in the next century in architecture? Just the continual anguish and reform and replanning and nobody, nobody knows what strange changes are going to take. The history of the past century, for instance. Nobody could have guessed what Le Corbusier would do, that what Frank Lloyd Wright did was to change the course of history, or Mies van der Rohe. And now the kids! We have a wonderful generation coming, twisting it all out of what an older person would think was shape. But they're doing it with such panache, with such verve, which such delightful humor, that a whole new panoply of architecture's opened up. That's why, as far as my feeling goes, it's all going to be good. The world can go to pot, as it seems to be doing very well thank you, but it doesn't affect architecture. The late Byzantine period may have been, toward the end of a bad period, but great churches that will always last and always inspire. So have the decadence that maybe is coming, but maybe not. If it's coming, architecture will go on anyhow. If it's not coming, architecture will go on anyhow and create it's own richnesses. You can't stop people from doing architecture. You can't stop people from writing poetry.

All right, the times go bad, the times go good, but the eternal things, like poetry or architecture, go on. And, they will go on. That is one of the great things about being connected to an art as great as architecture. It's your desire -- Plato's words -- desire for immortality. That's what keeps you going, not sex. It doesn't make any difference anyhow at my age, but it's not important as a drive, Mr. Freud to the contrary notwithstanding. Plato was right. Everybody has a desire for immortality. So when you die isn't very important. Because your immortality -- what did you do when you were here that made any sense?

I can't think of any better place to stop. Thank you. It's been a privilege.

You're welcome.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

disclaimer

architecturalinterviews.blogspot or any other blogs in this architectural series (theories, monographs, interviews, lectures, videos, books, magazines, standards, histories, accessories, architects) does not host any of the files mentioned on this blog or on its own servers. architecturalinterviews.blogspot only shares various links on the Internet that already exist and are uploaded by other websites or users there and also shows courtesy in the beginning of each post. To clarify more please feel free to contact the webmasters anytime or read more Here.

newer

newer older

older

0 comments:

Post a Comment